Tribolium Extraembryonic Development

Background

Embryonic development of most pterygote (winged) insects includes the formation and morphogenesis of two distinct extraembryonic epithelial sheets: the serosa and the amnion (reviewed in Panfilio 2008 and Schmidt-Ott et al. 2010). In Drosophila these tissues are secondarily reduced and have evolved into what is called the amnioserosa. Therefore, despite extensive literature on the Drosophila amnioserosa (e.g. Lynch et al 2013), other insect models such as the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Fig. 1) need to be explored in order to further our understanding of the development and evolution of insect extraembryonic membranes.

Tribolium castaneum develops two extraembryonic membranes. The outer membrane, the serosa, envelopes the embryo-proper, amnion and yolk. The amnion remains attached to the embryo and covers it ventrally. It follows that the amnion needs to open in order for the embryo to close dorsally. Indeed, at around 50-55 hrs after egg laying (AEL), the serosa and amnion rupture at what appears to be a predetermined position (at the ventral anterior of the egg). Shorty thereafter both membranes retract and form the so-called dorsal organ: a dense accumulation of apoptotic cells, dorsally on top of the yolk, in between the lateral flanks of the embryo that now gradually approach each other (initiating dorsal closure).

In order to study these morphogenetic process in Tribolium, our lab characterised several GEKU enhancer trap lines (Koelzer et al. 2014) [Figure 2]. One of these lines specifically expresses EGFP in the serosa (G12424 or "serosa" line) . A second line marks, among other tissues, precursor cells of the heart (G04609 or "heart" line). Enhancer trap lines are of particular interest for studies of the extramembryonic membranes, because it is very difficult to stain late embryonic stages with, for example, antibodies, due to the formation of cuticle. Also, these lines allow live imaging of the development of particular tissues in vivo.

Live imaging of Tribolium using conventional microscopy generally involves fixing a specimen in place and observing it from a fixed point of view. This static arrangement is not ideal for studying processes that are dynamic over a large area of the surface of an egg, such as extraembryonic morphogenesis, or major rearrangements of the embryo proper. Also, with conventional mounting methods, it is difficult to observe the surface of the poles of the longitudinally elongated eggs of Tribolium. Recent advances in selective plane illumination microscopy (SPIM) have the potential of solving these problems, as the optical arrangement of detection and illumination objectives in these microscopes has pushed the development of mounting methods that allow rotation of the specimen and hence multiview imaging.

Experiments

Five angle multiview time lapse

"This experiment was performed using the F1 progeny of a cross between female G12424 and male G04609 beetles, kept at 32 degrees according to standard methods.

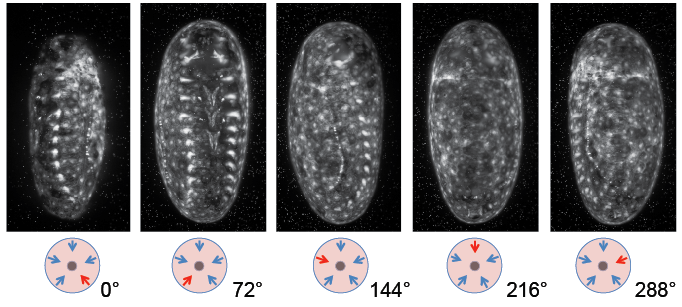

One live embryo, at about 50hrs AEL, was embedded in 1% LM agarose in a glass capillary (red label). It was then imaged on a Zeiss Lightsheet Z.1 using the 20x/1.0 detection objective, zoom factor 0.6x, with dual side illumination. Fusion of both illuminations was performed within the ZEN 2014 application ("live fusion"). The embryo was rotated around its main body axis in order to record five different angles, equally spaced over 360 degrees [Figure 3]. For each angle, a z-stack was collected ranging from just outside the embryo up to centre of the embryo. In other words, each stack covered about halve the embryo. In total, 73 time points were imaged at 5 minute intervals. Each angle and each time point were recorded as separate files. The resulting dataset had a total size of about 470 GB.

Data analysis

" "Data analysis was performed using Fiji plugins Multiview-Reconstruction and BigDataViewer. Initial analysis was done on time point 35, which would later serve as a reference time point for the whole time lapse. As a first step, files were converted from .czi to .tif, and maximum intensity projections were made for each of the five views [Fig. 4].

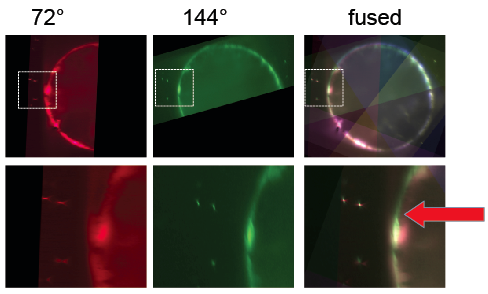

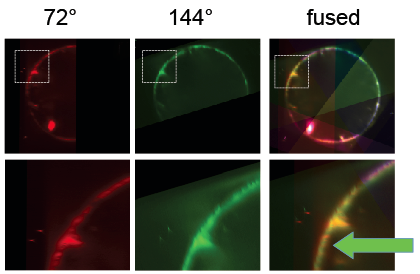

Next, beads were detected and used to register the stacks taken from different angles. Subsequently, the BigDataViewer plugin was used to visualize the registration. When different view colors are set for the different angles, it becomes apparent that the bead based registration did not perform perfectly: beads are registered well, but the different views of the embryo appear slightly non-overlapping [Fig. 5]. Segmentation based registration turned out to be clearly better for this dataset [Fig. 6].